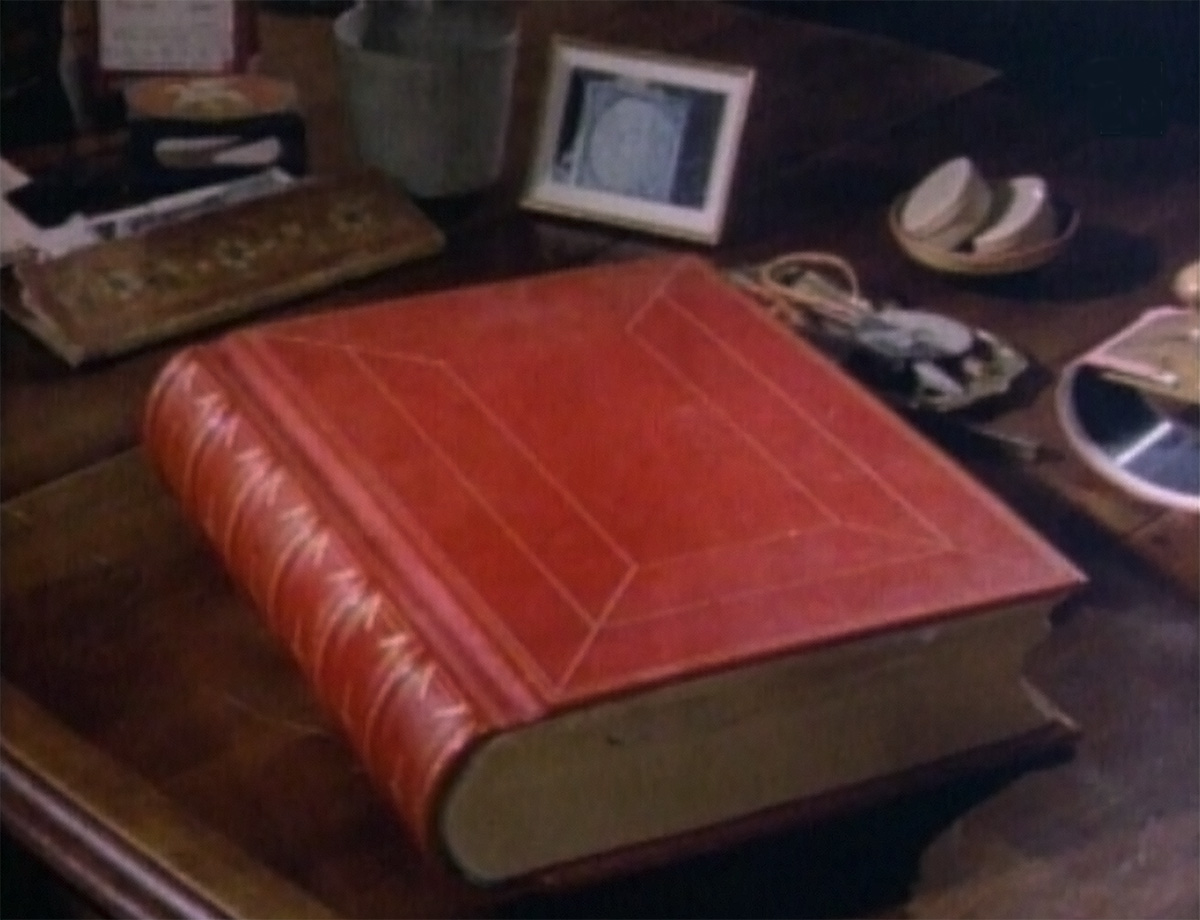

Using the Red Book to visualize in 2016

The Red Book (Liber Novus) by C. G. Jung, resting on Jung office desk. SOURCE: LOwens at English Wikipedia

Carl Jung’s personal exploratory work, the Red Book, sat on his desk yet was hidden from public view for over 80 years; it was carefully photographed and published in facsimile (with an English translation and extensively researched notes) in 2009, and though I did get to see the original, along with some of the preparatory artwork Jung created that later was refined and put into the book, I just started the deep dive into the work, timed at first coincidentally and then purposefully, at Christmas.

The book starts with “Liber Primus: The Way of What Is to Come“; opening with bible passages in Latin, first from Isaiah 53:1-4: “…Who hath believed our report?”, then Isaiah 9:6 “For unto us a child is born..”, next, from John 1:14 “And the word was made flesh” – (a standard reading for Christmas liturgies).. and finally, again from Isaiah, “… Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened”.. after which, he launches into his personal inquiry into understanding himself as a gateway to understanding the nature of humanity.

And he did it through visioning as much as through the written word; he explored the visual symbols of his dreams, his hallucinations, and his own images (with great use of drawing and painting mandalas, derived from Eastern spiritual mysticism).

Was Jung a “Design Thinker”?

The book was never clearly intended for publication. Like DaVinci’s notebooks, they were the personal classrooms of thought and learning, combining visuals with words to summon both the raw material of the imagination and then the synthesis of that into both knowledge and art; or, rather, art-like representation of that knowledge that words cannot express. I say “art-like” because although each image might be seen as individual works of art in their own right, they are part of a larger form of communication. (Look at Nick Sousanis’ Unflattening, for more about the flow of storytelling communication combining words and images.)

Jung spent decades working on the book, starting in 1913, transcribing dreams into it, writing in various calligraphic styles, and adding artwork. Little, if any, of what is in the book was put there spontaneously. There are five sources for the text, and preparatory works or studies of the art are also extant. It has flavors of Medieval manuscript as well, with decorated first letters opening sections of the first of the three parts in particular.

The first section, prophetic in nature and full of fantasy, opens with and champions the exploration of the individual, searching artifacts in “the spirit of this time,” which speaks of “use and value” (don’t we speak about that constantly in design thinking?) and then, underpinning everything, the “spirit of the depths”, where universal truth and inherent nature reside; we might consider “affordances” and “heuristics” to possibly live on one side or the other of these spirits.

In design thinking, particularly Human-Centered design, with its focus on “Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation” rooted in a unrestricted search for creativity followed by short experiments to see how each iteration works for real people, there is the firm belief that correct and truly useful solutions will emerge. It is dependent on constant focus and interaction with people, and defining personas, from the make-up of archetype to their specific patterns of behavior, is at the core of HCD. Jung’s work paved the way to understanding what archetypes are, and in the heart and depths of the Red Book we witness his wrestling to know both the glorious and the ugly, the orderly and the chaotic of himself, and, through this, all of us.

Why draw when you can write?

Some of Jung’s early experimentation into self-discovery came through going into a state where the unconscious could emerge and then be examined for clues, metaphors, symbols and archetypes. By going into a partially awake state he could let the realm of dreaming surface while still being able to observe and record what was going on. Automatic writing was one method of opening the doorway, but attempting to understand his dreams and hallucinatory visions from the unconscious that he summoned in a “waking state fantasy” required capturing them as they came to him: as images. And while this is challenge for all of us, it tells us why making pictures matters.

While he considered this deeper part of the mind the source of creativity, (which even the most “non-visual” developer should wish to access to discover the patterns and code to make amazing environments/sites/mobile experiences/games/etc), it also is where the spirit of both the individual and the connection to what became called the collective unconscious resides. No wonder it is a jumble of both recognizable and unrecognizable forms, shapes, colors, object, people. Sometimes the content appears as recognizable landscapes, people we know, figures and models that stand in for others, where time bends to the mercy of whatever story is being told. Words often can hardly do justice to the fantastic images that appear.

We work constantly towards making “dreams come true,” “sharing our vision”, or avoiding “living in a nightmare” – all visually-driven metaphors. Are icons, logos, and even pictures intended to be documentation sometimes unclear and less specific than words? That depends on how exact words are, and how much we trust that others will comprehend what our words mean to us.

However, our visual capabilities reach beyond the flatness of the written word, which comes to us in linear fashion and needs to be interpreted. Through the image, when we’re in sending mode we can instill information, while in receiving mode we interpret what we see in far less time and greater depth than we can with a declamatory paragraph.

Creating images, therefore, even sketching and doodling, can be more effective than writing. Jung created text and images tied together in the Red Book, with deep commitment to stylized forms for both. 53 pages are strictly images, while 71 pages contain both text and artwork and 81 pages are entirely calligraphic text, all done by hand. The pictures are filled with symbolism, particularly the mandalas and the Hieronymus Bosch-like tableaus.

Jung needed to make these pictures as part of his exploration, and that in itself is a great inspiration.

It’s all about the user

Jung didn’t refer to patients in this work, much less “users”, “clients”, or “web visitors” when summarizing thoughts-feelings-behaviours-actions of people engaged in similar experiences, environments and states. In the Red Book he seeks to know about the timeless and universal constants in humanity. He wanted to understand how it could be possible that he could imagine and visualize things and come up with his own habits as a child in Switzerland, which he believed at first to be of his own making, that could also be imagined and performed by native tribes people thousands of miles away. Are there certain things that are inherent in all human thinking, feeling, understanding? Are there beliefs, symbols, totems, rituals that are transcendent language, culture and place? Can Google’s concept of “moments” be turned into an algorithm that will work in any/every language for people all over the world?

Jung’s lifetime exploration of that commonality, the collective unconscious, shows up in the study of mental models, although perhaps stripped of some of the spiritual and mythological language expressed throughout the Red Book and his published material. We may not hear much about “the great mother” or the “trickster” in books written in the last 10 years about mental models, but we are fine talking about Centrality vs Diffusion, Order vs Chaos, and Opposition vs Conjunction. And when we talk about opposing forces, it falls naturally into some kind of diagramming, even as simply as placing words side by side in lists, so we are, once again, resorting to visualizing how these models work and how these stories are played out. Which leads me to why go into the Red Book, this year with it’s mix of hallucinatory visuals, Socratic dialogue, referential tributes to Dante’s Inferno, and artwork as dream-based yet reflecting a new examination of the order of things as any painting by Kandinsky.Understanding us and our stories

It comes down to the story, told in pictures and words of the Red Book, of a quest to find oneself, the individual, within that mix and mess of contradictory thoughts and sea of emotions, that draws me in and makes me want to follow. It is a Hero’s Journey, and though it isn’t my own exactly, It is my hope that Jung’s revelations, even when they just open the way to more questions, will inform and inspire me, particularly in my work for others, to both see and show more clearly whatever it is I or they wish to say.

I would hope that my own form of a Red Book may be starting here, in this post and continue through other posts and other media, with my version (or my archetypal version that I’ve created here) of Jung serving as my Philemon, the wise spirit guide, who shows me a way forward.

![1913 - Composition 6 by Wassily Kandinsky [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3a/Vassily_Kandinsky%2C_1913_-_Composition_6.jpg)