What’s Wrong With This Picture?

How doodling helps shape the unseen, abstract principles in order to create

real meaning.

—-Brian Tarallo

[youtube url=”http://youtu.be/w6emKsn3WIU” fs=”1″ hd=”1″ rel=”0″ showsearch=”0″ showinfo=”0″]

What if you could see an idea? What if you could hold an idea in your hand

and shape it until it became solid and defined? Until it becomes so clear

that other people could understand it just by seeing at it? If you’ve ever

had the feeling that you KNEW something but just couldn’t find the words to

explain it, you can imagine how powerful seeing an idea would be.Now: what if I told you that nearly everyone is born with this ability to

see ideas, that YOU have it, and yet for some reason, you are told by your

teachers, bosses, and maybe even your parents…

…to knock it off?Up to now, you’ve seen me taking visual notes of the amazing talks we’ve

heard today. You probably had a few reactions: “What the heck is that guy

doing?” Or maybe, “Oh, I get it: that’s pretty cool.” And maybe, “Hey, I

think I could do that!”Well good news: I’d like to invite all of you to engage with the rest of

this talk in a way that might be new for you. Please take out the notebooks

and pens you were given, and DRAW WHAT YOU HEAR. Take visual notes. Don’t

try to capture everything you hear, just what stands out for you. Write a

short phrase and draw a quick icon representing that idea. Just try it. You

have a quick startup sheet from my colleague, Mike Rohde, with techniques

for this. And if you don’t want to take visual notes, please doodle. It’s

OK, you won’t have to show it to anybody, and I promise I won’t take it

personally if you’re not staring at me.As you get started, I’d like to begin with a question: What’s wrong with

this picture? What’s wrong with doodles? Why don’t we let kids doodle in

school? All children doodle. It comes naturally. It requires no

instruction. And yet we tell them NOT to do it. Why? I was the kid who

always had two pieces of paper on my desk: one for notes, and one for

doodles. I got in trouble a lot. Especially in Algebra.

I was told: “you’re not paying attention.” “That’s useless.” And “this

isn’t art class.” Today, I doodle professionally. And more than that, I

give people tools to help them see ideas, visual tools based on doodles to

solve really hard problems, problems that would be impossible to solve any

other way. So why do we teach kids that doodling is wrong?I believe doodling is today what left-handedness was not so long ago. My

grandfather was left-handed. His teachers would beat his knuckles with a

ruler if he didn’t use with his right hand. He got by, but as a result, he

developed a stutter. He got out of school, started writing with his left

hand, and immediately lost his stutter. But: I can’t help but wonder what

school would have been like for him if he’d simply been allowed to write

with his left hand, to do what came naturally.As a father of four kids who are just beginning their education, my biggest

fear is that schools will ignore the fact that different children learn in

different ways.My colleagues Sunni Brown and Rachel Smith have spoken at TED conferences

before about the power of drawing ideas. Take a note: check out their TED

videos. Sunni Brown and Rachel Smith. I’d like to build on their thoughts

along those of other visual practitioners, like Diane Durand and Dean

Meyers, who continue to evolve the conversation around using visuals in

education, healthcare, and business. I’d like to talk about why I believe

doodling can help engage students in learning, ready them for a complex

world, and make school fun. And I’d like to do so by turning the three

biggest misconceptions about doodling on their heads: that it’s

distracting, that it’s useless in the real world, and that it’s only place

is in art class.First misconception: it’s distracting.

Doodles are black and white proof of a wandering mind. They are inescapable

evidence that “you weren’t listening.” And if you weren’t listening, how

could you have been learning?So here’s what we know. We learn by seeing, hearing, and doing. You’ve

heard of the visual learner, the auditory learner, and maybe you’ve heard

of the kinesthetic, or motion-active, learner. It turns out that no one is

purely one kind of learner. EVERYONE has SOME aspect of each of these

learning styles, and the more that you engage ALL of the learning styles,

the greater your understanding and retention. Doodling engages all three

styles. A doodle doesn’t even have to be related to the subject matter to

engage the kinesthetic learner. I love this quote by Sunni Brown: “there is

no such thing as a mindless doodle.” A study of people listening to

complicated phone messages found that doodlers retained 29% more content

than non-doodlers. Did you get that? Doodling keeps you from losing focus

when the topic is boring. Which is why I asked you to draw while I was

talking.But when the doodles ARE relevant to the subject, you make a personal

connection with what you are hearing. You think: what does this concept

remind me of? What does it look like? What can I draw that represents it?

What metaphor could I use to illustrate it? You become an active learner.

You create an experiential memory that allows you to make connections and

see patterns that would have been invisible to the passive learner.

We learn by doing and we learn by doodling.Second misconception: it’s useless in the real world.

It’s not professional. You don’t need it to do your job. Your boss isn’t

paying you to doodle.Okay, for right now, we’re going to ignore the following professions:

visual practitioners like me, artists, illustrators, architects, engineers,

creatives, designers of all kinds, and anyone else who draws as part of

their job. Instead, we’ll focus on what my algebra teacher called “real

jobs.” Ever seen this before? It’s been called “The most famous napkin in

Texas.” It’s Herb Kelleher’s concept for the original business model for

Southwest Airlines, and it was literally drawn on the back of a napkin.

There’s a book about that if you’re interested. It’s called “Back of the

Napkin.”Regardless of what your job is, chances are you have to solve hard problems

or communicate complex ideas. Doodles are the pure language of ideas. One

of the pioneers in the field of visualization, David Sibbet, likes to say,

“you don’t build a house from a set of instructions. You use a blue print.”

When an idea is complex or ambiguous, words lose their effectiveness, and

visuals become more effective. Think about the last time you sat through an

80-slide PowerPoint deck, or read a 100-page strategic plan. How much did

you really retain? The University of Stanford studied the use of

collaborative, participatory group visuals in meetings and found that they

increase retention by 17%, improve consensus by 19%, and actually shorten

the time it takes to solve problems by 24%. Unfortunately, just putting

clip art in PowerPoint doesn’t count. This is about using visuals as a

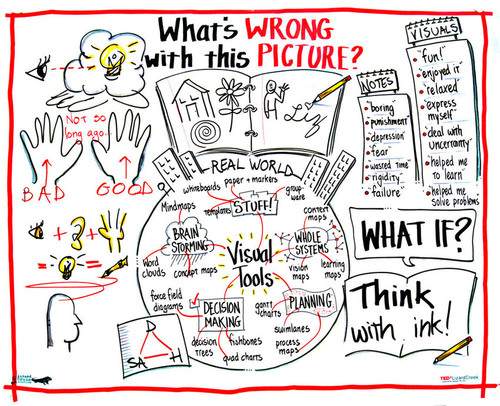

medium to gather ideas, solve problems, and plan the way ahead.I want to take a minute and give you a quick list of visual tools you can

look up later that can cut through ambiguity and solve hard problems.

You have your brainstorming tools, like mindmaps, word clouds, and concept

maps.

You have decision making tools, like force field diagrams, decision trees,

fishbones, and quad charts.

You have your planning tools, like gantt charts, swimlanes, and process

maps.

You have your whole systems tools, like learning maps, vision maps, and

context maps.

Plus, there’s all the cool STUFF that you use: whiteboards, groupware,

templates like the business model canvas or the graphic gameplan, and my

own personal favorite, paper and markers.What I just demonstrated is a tool called a mindmap. In my opinion, a

mindmap is the single greatest tool for brainstorming ideas, period. THIS

is something we should be teaching in school. You start with a central idea

and you branch outward, following key ideas as they occur. You move up and

down in levels of detail, adding new branches, going wherever your mind

takes you. You draw cross connections as ideas interrelate. One idea will

suggest another. You can imagine how powerful tools like these are in the

real world.Third misconception: This isn’t art class. This isn’t the time or place.

We’re not teaching art here.Let me ask a question: at the end of the day, what’s the point? Do you want

kids to have nice, neat, clean, sterile notes that copy verbatim what the

teacher says? Or, do you want kids to make sense of what they’re learning

and retain it? It’s THEIR notes. Let them take notes in a way that they’ll

remember. And yes: kids still get in trouble over this today. So do

grownups, for that matter.I’m not suggesting kids draw all over their homework or their tests or

anything they have to turn in. But how cool would it be if students turned

in a mindmap along an essay so teachers could actually see the thought

process that went into the final product? Isn’t teaching kids how to think

the point of school in the first place?

There’s two studies I want to share with you on note taking. Tony Buzan,

one of the world’s leading authorities on learning techniques, asked

students what words they most associated with note taking. The top seven

were: boring, punishment, depression, fear, wasted time, rigidity, and

failure. THAT is how students feel about how they spend most of their time

in school. And it doesn’t have to be like that. By the way, Buzan went on

to create a new style of notetaking that he called, “mind mapping.”The other study I want to share is by Doctor F. Robert Sabol of Purdue

University, who looked at the effects of No Child Left Behind. You can

probably guess some of the findings: more of discipline and behavioral

problems, apathy and resentment, decreased work ethic, but here’s what was

surprising. When it came to drawing or other visualization, students

reported that it was “fun.” How about that? Students drew because they

enjoyed it, it relaxed them, they felt like they could express themselves,

it helped them deal with uncertainty, and that it helped them learn new

things and solve problems. NO KIDDING.So here comes my favorite question of all time: what if? What if students

were allowed to take visual notes in all their classes? What if we stopped

telling kids not to doodle? Because maybe the biggest loss here is that

kids who are told to stop doodling in class grow up to be adults who say

things like, “I’m not a visual person,” or “I can’t draw.”“I can’t draw.” I want to do an experiment. This is a quick exercise I

learned from my friends at kommunicationslotsen, a German visualization

firm. Germans have some of the coolest stuff. These markers? German! OK:

take a deep breath. Release. Again. Close your eyes. I can see all of you,

I know who’s cheating. In your mind, I’d like you all to go back to when

you were a student. Think of yourself sitting in class. On your desk, there

is an open notebook. And in that notebook, there is a doodle. There was

always one doodle, one drawing, one picture you drew. You drew it over and

over and over. Now: open your eyes. Find a blank page in your notebook, and

draw that doodle.Here’s what most people draw: an object, a person or a face, a word,

something abstract, or something from nature. What do they have in common?

It’s not what you would call fine art, but that’s not the point. It’s

quick. It uses simple shapes. It’s iconic. It’s a symbol for an idea.

That’s not what a house actually looks like, and yet, people know it’s a

house. It is the IDEA that matters most. When you use simple shapes and

simple icons, you have everything you need to take visual notes.Let’s do one more what if. What if you’re a teacher and you catch a student

doodling in class, or you’re a boss and you catch an employee doodling in a

meeting? Your first thought will be that they’re distracted and not paying

attention. It’s OK: despite everything you’ve just heard, you’ve been

trained your whole life to believe doodling is bad. But now, you know

better.

And then, ask yourself: What’s the point? What’s important to you? Do you

want them to sit still as statues, eyes wide and locked on you? Maybe a

little drool going on? Or, do you want them to maybe learn something? 51%

of us are introverts. 29% of us are predominantly visual learners. 37% of

us are predominantly kinesthetic learners. With those numbers, chances are

more than a few of your listeners would really hear what you have to say

better if they were doodling.Here’s the message I want to leave you with. Doodles help you learn better.

Doodles have real world application. And doodles can make learning fun.

Anyone can do doodle, because at its core, it’s not about artistic skill.

As you probably noticed as you were taking visual notes, the real skill is

listening and making a personal connection to the content.

And here’s what I would ask of you. Think with ink. Think, what’s RIGHT

with this picture. If you have a pen in your hand, draw. If you’re a

teacher, a parent, a caregiver, a manager, or a leader, create a space

where doodling is OK. I honestly believe that I have the best job in the

world: I help people see ideas. When you create a space where doodling is

OK, you allow others to see ideas, too.Thank you.

Brian Tarallo doesn’t just talk a winning argument for doodling, he doodles it, live, in front of a group of people at TEDx . I cannot speak for the participants whether or not he has convinced them of the benefits of doodling on learning, memory, creativity and reasoning skills, but he does back it with studies on education and learning styles.

I would recommend reading the text of his talk while looking at the finished graphic he created, and see if you are able to put the two together, as he uses visuals and key text to illustrate his talk.

The proof of his theory, however, will be demonstrated if you adopt his suggestion of using doodling, sketching and personal note taking with visuals whenever and wherever you need to capture information, reason through a problem or feel more engaged at a meeting or creative activity.

See on lizardbrainsolutions.com

[…] What's Wrong With This Picture? How doodling helps shape the unseen, abstract principles in order to create real meaning. —-Brian Tarallo What if you could see an idea? What if you could hold an idea in your hand and shape it until it became solid and defined? Until it becomes so clear that other people could understand it just by seeing at it? If you've ever had the feeling that you KNEW something but just couldn't find the words to explain it, you can imagine how powerful seeing an idea would be. Now: what if I told you that nearly everyone is born with this ability to see ideas, that YOU have it, and yet for some reason, you are told by your teachers, bosses, and maybe even your parents… …to knock it off? Up to now, you've seen me taking visual notes of the amazing talks we've heard today. You probably had a few reactions: “What the heck is that guy doing?” Or maybe, “Oh, I get it: that’s pretty cool.” And maybe, “Hey, I think I could do that!” Well good news: I’d like to […]

[…] What's Wrong With This Picture? How doodling helps shape the unseen, abstract principles in order to create real meaning. —-Brian Tarallo What if you could see an idea? What if you could hold an idea in your hand and shape it until it became solid and defined? Until it becomes so clear that other people could understand it just by seeing at it? If you've ever had the feeling that you KNEW something but just couldn't find the words to explain it, you can imagine how powerful seeing an idea wou […]